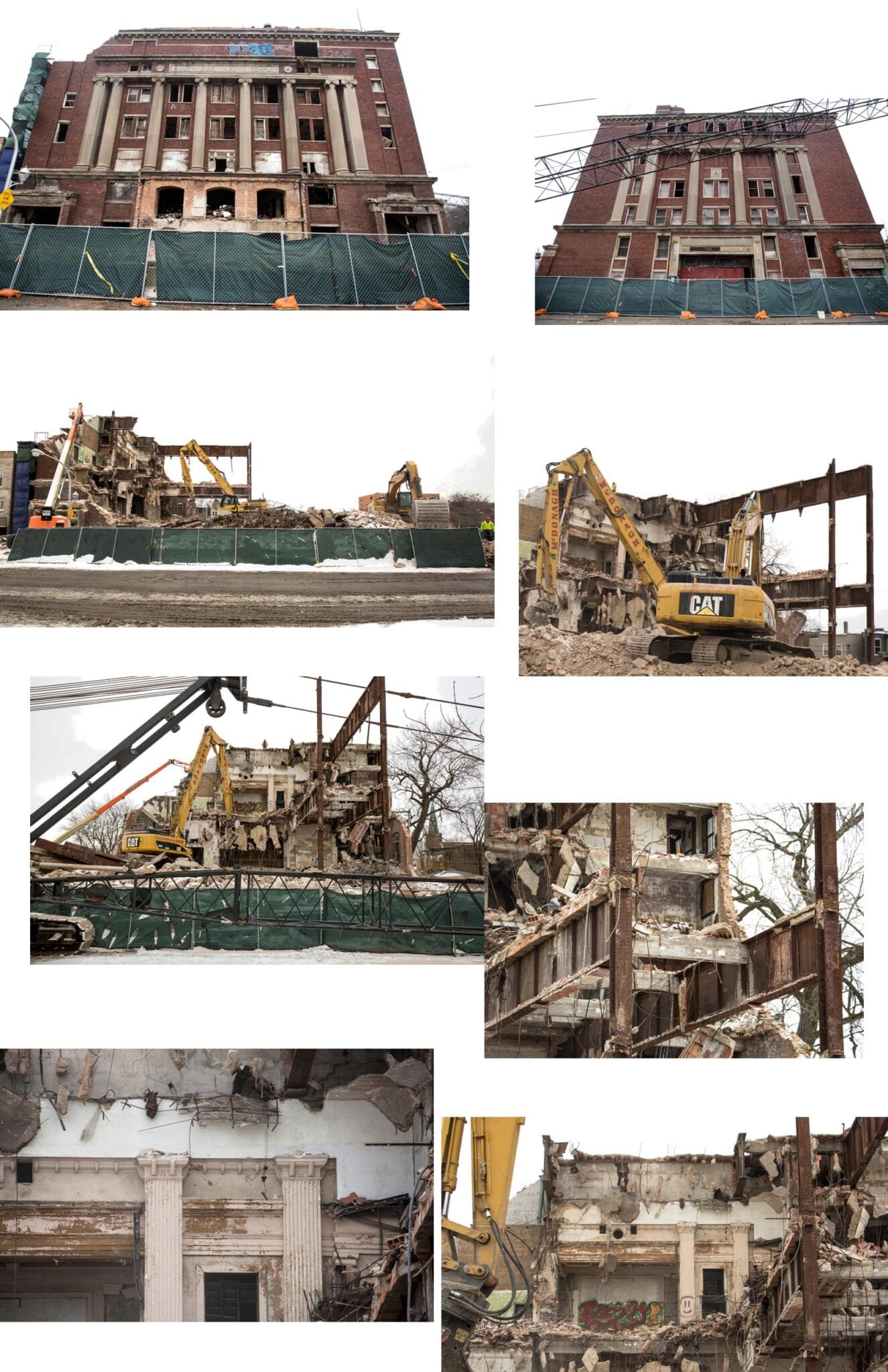

demolition nearing its end on clarence hatzfeld's south masonic temple building

This entry was posted on February 10 2018 by Eric

by eric j. nordstrom & ornament chicago

very little remains of south side masonic temple (1921). a few riveted joint steel trusses and columns, partially covered with chunks of dangling concrete, will be pulled apart with the wrecker's long reach excavator this week.

remnants of a grand hall bedecked with ornamental plaster (e.g., fluted pilasters) cling to life on the battered south wall. the temple's time capsule is likely buried deep within the rubble. most of the exterior bedford limestone ornament - designed by the building's architect clarence hatzfeld - has made its way to the landfill.

surveying the slate grey wreckage of limestone on this bleak february afternoon it’s both difficult and easy to imagine the attraction to this stone. on one hand its uniform homogeneity is very much appealing. on the other, its dull neutrality seems endless, uninspiring, and certainly lacks the subtle hues of other stones.

reflecting on the years after the world’s columbian exposition (1893) and the return of classical revival architecture as reintroduced by daniel burnham with the “white city,” bedford limestone appealed to tastes at the time. classical buildings demanded uniformity and clean lines, and bedford limestone fit well within the formula for this architecural style.

limestone was much cheaper than marble for classically inspired buildings, and there was ample supply to fuel the building demands of a city still growing at a strong clip. most of the chicago buildings made from bedford limestone described in part 6 were built in the early to mid 1920s.

by the end of the decade, however, the great depression halted demand. during world war II shortages of steel and other building materials forced the adoption of prefabricated materials and rapid changes in building technology occurred thereafter. the use of elaborate ornament fell from favor with the “less is more” aphorism associated with mies van der rohe and the streamlines of other modernist architects.

by the 1950s many quarries had begun to shut down. the advent of stark, simplistic buildings with steel skeletons crippled demand for limestone. as of today there are only five active limestone quarry companies remaining in the bedford area. their projects involve cathedrals, state buildings, and universities, as well as less grandiose productions such as garden terrace blocks and edging stones.

most quarries in the bedford area, however, are long discontinued. the era of indiana building limestone, like its predecessor illinois limestone, has largely come to an end.

rondels, plaques, tablets, and pillars like the ones that graced the south side masonic temple are no longer produced by highly skilled stone cutters like the ones that adorned this building, because the skills they possessed also passed away with these same craftsmen. in short, it’s a travesty their contribution hasn’t been preserved.

as a further insult to the indifferent disregard for preservation and further study, the removal of this building’s remains to the landfill represents yet further waste. dimension stone is typically reusable and can be salvaged for new construction. in the event significant erosion or weathering has occurred, tests can done to see if salvaged material is fit for reuse as a structural material following refinishing.

if buildings such as this one were deconstructed and components reused then new structures would potentially cost less and consumption of resources used to fabricate new products could be avoided. steel, concrete, and laminated plastics all require tremendous energy to produce as opposed to a natural, earth friendly product such as stone. and as the 'the natural stone council' suggests, light colored stone is often overlooked as a way to increase energy efficiency due to its ability to reduce heat-island effects.

sadly, and unlike other popular materials which are routinely “reclaimed” such as barn wood, there is no present organized system for recovering and reselling large scale dimensional building stone, so most of it winds up in the landfill.

this is especially egregious given that even if it was not recovered to be used in old stone building renovations, fireplace mantels, statuary, benches, or retaining walls, it could still be used as paving material or crushed for use as concrete aggregate, gravel fill, or landscaping.

watching the trucks haul away the remains of this 300 odd million year old stone quarried on the backs of countless men in the bowels of the earth itself, it all struck me as such a colossal, preventable waste.

highly skilled craftsmen carving stone

in the final post of this eight part series which we hope to publish shortly, we'll return to bid a final goodbye to the south side masonic temple with the recovery of the time capsule.

note: the two images below (east and south facades respectively) revisit the building shortly after demolition began at the beginning of the year. the hand carved bedford limestone rondels were carefully extracted, but the gargantuan columns, capitals, and name plaque now reside in the landfill.

This entry was posted in , Miscellaneous, Salvages, Bldg. 51, Events & Announcements, Featured Posts & Bldg. 51 Feed on February 10 2018 by Eric

WORDLWIDE SHIPPING

If required, please contact an Urban Remains sales associate.

NEW PRODUCTS DAILY

Check back daily as we are constantly adding new products.

PREMIUM SUPPORT

We're here to help answer any question. Contact us anytime!

SALES & PROMOTIONS

Join our newsletter to get the latest information