eric j. nordstrom's workers cottage efforts featured in urban design blog curbed chicago

- latest images from ongoing photographic documentation of pilgrim baptist church reconstruction by central

- theodore karl's 1872 conrad seipp post-fire chicago three-story commercial building (1872) undergoing demolition

- threatened: jens j. jensen's 1925 spanish baroque style pioneer arcade building terra cotta facade on pulaski

- 2024 exterior photographic survery of terra cotta ornament on purcell, feick, and elmslie's merchants national bank

- exterior photographic survey of frank lloyd wright's 1901 frank w. thomas house

Categories

-

Default Category

- Sale Items

- Products

- Architectural

- Collections & Trends

- Artifacts & Accessories

- Lighting

- Furniture

- Museum Quality Artifacts

- A. Finkl & Sons Chicago Foundry Objects & Artifacts

- Chicago Athletic Association Building Artifacts

- 19th century Sidewalk Vault Lights

- Historic Building Terra Cotta

- Sullivanesque Building Terra Cotta

- Reliance Building

- Daniel Burnham's Fisher Building

- Chicago Stock Exchange Building Artifacts

- John Kent Russell House Artifacts

- Odin J. Oyen Collection

- Richard Nickel Photography

- Louis Sullivan

- Frank Lloyd Wright

- Gardenesque

- Michael Reese Hospital Artifacts

- New York City Subway Artifacts

- BLDG 51 Museum Book

- Previously Sold

This entry was posted on August 27 2019 by Eric

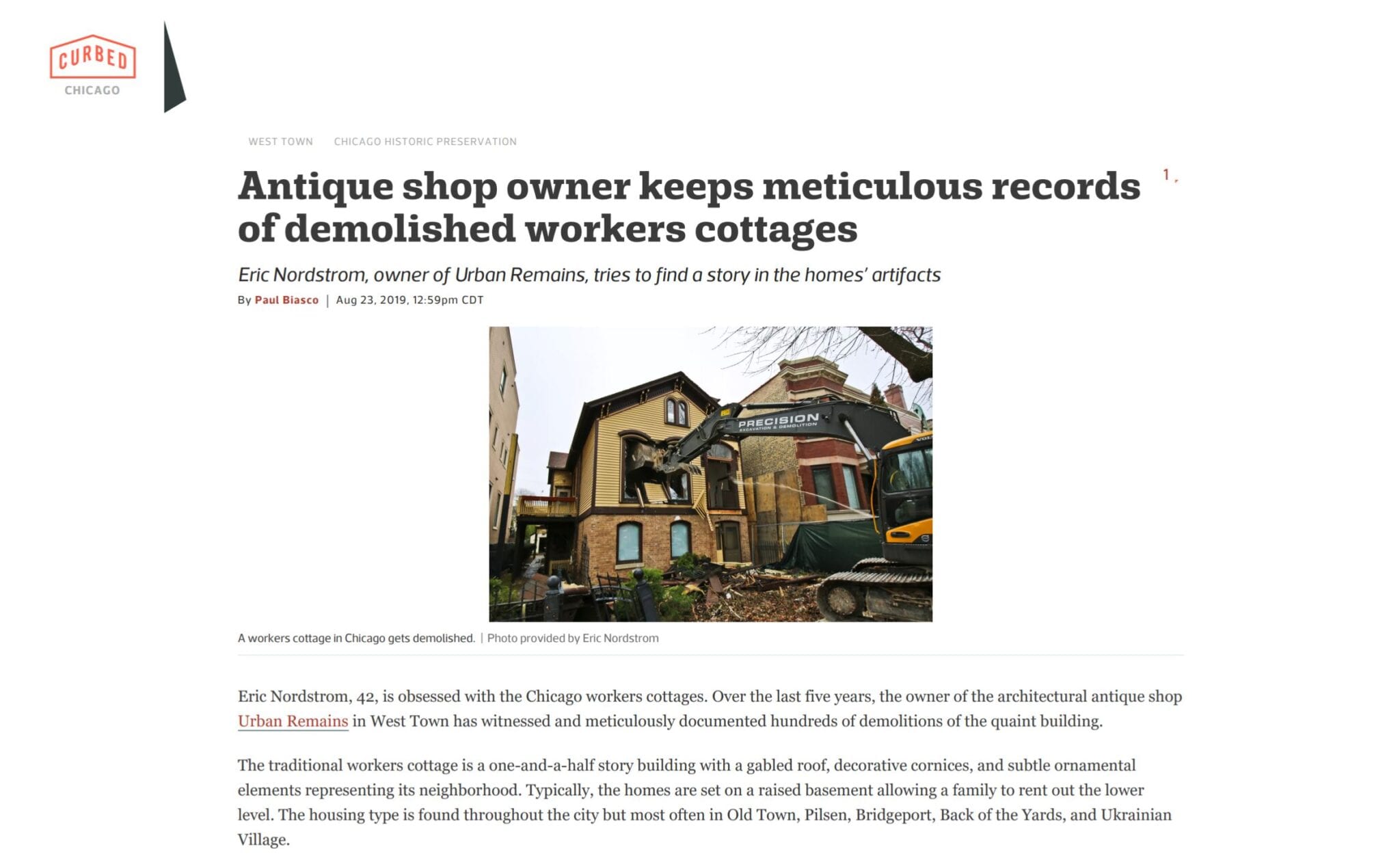

Eric Nordstrom, owner of Urban Remains, tries to find a story in the homes’ artifacts

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/65098608/20170228_4V0A4911.0.jpg)

Eric Nordstrom, 42, is obsessed with the Chicago workers cottages. Over the last five years, the owner of the architectural antique shop Urban Remains in West Town has witnessed and meticulously documented hundreds of demolitions of the quaint building.

The traditional workers cottage is a one-and-a-half story building with a gabled roof, decorative cornices, and subtle ornamental elements representing its neighborhood. Typically, the homes are set on a raised basement allowing a family to rent out the lower level. The housing type is found throughout the city but most often in Old Town, Pilsen, Bridgeport, Back of the Yards, and Ukrainian Village.

Nordstrom has obsessively dedicated himself to documenting, and attempting to slow, the destruction of this humble part of Chicago’s history. He makes records of the demolitions with photographs, collected items, and written histories. Nordstorm’s commitment has earned him a reputation among wreckers who now regularly tip him off to upcoming demolitions.

“Time and time again these cottages are being destroyed and no one is really documenting them on a regular basis,” Nordstrom said.

Nordstorm is part historian, part scientist, and part salvager. He studied molecular biology in graduate school and that experience informs how he approaches each record of destruction: with scientific rigor.

He likes to head to the site early to photograph and document the home on its last day, stand by as a final witness, and then walks through the wreckage to find clues of its history (including into the long-forgotten privy pits, a deep hole below former outhouses in pre-plumbing days of Chicago).

He looks for age-markers to date the building such as newspapers or insurance documents, and more importantly the wooden materials that tell the story of construction techniques and technologies of Chicago’s early buildings.

“I approach that whole thing from a very scientific method. It is as if I was back in the lab,” he said. “I was collecting data, labeling pieces, comparing them to other things I would abstract from other cottages.”

And then back in his studio, he pieces back together the home considering construction methods and building materials.

“I’m sitting on a mountain of research. Images. Data. I haven’t tossed any of it. I have piles of studs and stones everywhere. Hundreds of thousands of images,” he said.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19099631/ericcolor.jpg)

Nordstrom’s obsession started with one demolition in particular: the John Kent Russell House . While Nordstrom was in graduate school pursuing his science degree, he began cataloguing homes in his Wisconsin neighborhood from the 1800s on a spreadsheet. When the Russell House was scheduled for demolition, he made a deal with the developer to let him inside to archive and collect the home’s artifacts. He recounts the event on his shop’s blog as what “dramatically altered the course of my life’s work.”

Nordstrom left with 3,000 photos and the construction artifacts that illustrated the history of the John Kent Russell House. The following year, Nordstrom’s private Bldg 51 Museumpartnered with the Clark House Museum to organize an exhibition of early Chicago building systems using photos and pieces of the home during the first edition of the Chicago Architecture Biennial.

The modest workers cottage dates back to before the Great Chicago Fire in 1871. It features an uncomplicated construction, common materials and could be built by homeowners themselves, said Ward Miller, executive director of Preservation Chicago.

“You walk past them and you can almost feel their service and their dedication to the families that occupied them,” Miller said. “They almost feel like they tell as great story of the people of Chicago.”

The workers cottage was one of the city’s original homes, built as early as 1830. First constructed with wood, and then after the fire with brick. Some of the most spectacular examples of the workers cottage existed between Lincoln Park and Old Town around Orchard Street, where developers have scooped up multiple lots to make way for double-wide mansions over the past 20 years.

“Orchard now is almost unrecognizable,” Nordstrom said. “All of the cottages there have been wiped out and replaced with these multiple lot McMansions which are disgusting.”

In that area of Lincoln Park along Orchard, Burling, Orchard, and Howe streets, there are a few pristine examples of post-Chicago Fire brick workers cottages. But, there are some homes that have retained their original elements.

“When you go to Old Town and you see the restored version with the grand wooden staircases and painted beautifully in historic colors... you just look at them and go ‘oh my gosh,’” Miller said. “How can something so simple be so beautiful and wonderful and captivating.”

When Nordstrom investigates a house he saves materials like wooden studs, shingles, pegs, nails, and beams. His lab-like office turns into a puzzle of countless pieces where Nordstrom immerses himself.

The “dissection” of each building is Nordstrom’s job. He wants to learn the story of its construction, the history of changes, and find other clues.

In 2016, Nordstrom studied two workers cottages at 1622 W. Erie St. in West Town that had undergone a number of renovations. He learned the buildings were constructed in the mid-1860s by studying materials like the sheathing, studs, and types of nails. He also compared construction methods like the use of wooden pegs, posts, and beams versus the more modern balloon frame style. The bones of the structure, while similar, is a clue to its story.

“Every cottage, every one, was an opportunity for me to open up the walls and see what’s there,” he said.

Sometimes Nordstorm said he feels hopeless trying to save workers cottages, especially when other styles have representation like the Chicago Bungalow Association and, until last year, the Chicago Greystone and Vintage Home Program. So this spring, Nordstrom announced plans to form the Chicago Workers Cottage Association which plans to more officially research, document, and preserve the building type’s legacy.

“Their eradication from the cityscape means the silencing of one Chicago’s greatest architectural contributions,” he says.

The association is still coming together and Nordstrom is looking to build his board and a team of allies who can help in his current quest. He’s also working on turning his mountain of research into a book, because for Nordstrom its most important that the data exists.

“I will continue protecting and advocating for cottages. That’s something I will do until I die,” Nordstrom said.

NEXT UP IN CHICAGO HISTORIC PRESERVATION

- This weekend, explore Chicago’s endangered architectural treasures by bus

- Union Station food hall, new Clinton Street entrance moves forward

- Landmarked Ukrainian Village church starts new life as high-end condos

- Mies van der Rohe’s Promontory Apartments gets preliminary landmark status

- Zoning changes aim to preserve Milwaukee Avenue and St. Adalbert church

- Auditorium Theatre wins award for extensive, decades-long historic preservation effort

This entry was posted in , Bldg. 51, Events & Announcements, Featured Posts, Bldg. 51 Feed & Press on August 27 2019 by Eric

WORDLWIDE SHIPPING

If required, please contact an Urban Remains sales associate.

NEW PRODUCTS DAILY

Check back daily as we are constantly adding new products.

PREMIUM SUPPORT

We're here to help answer any question. Contact us anytime!

SALES & PROMOTIONS

Join our newsletter to get the latest information