analysis of post-fire stone used to rebuild structures within the "burnt district"

This entry was posted on December 10 2019 by Eric

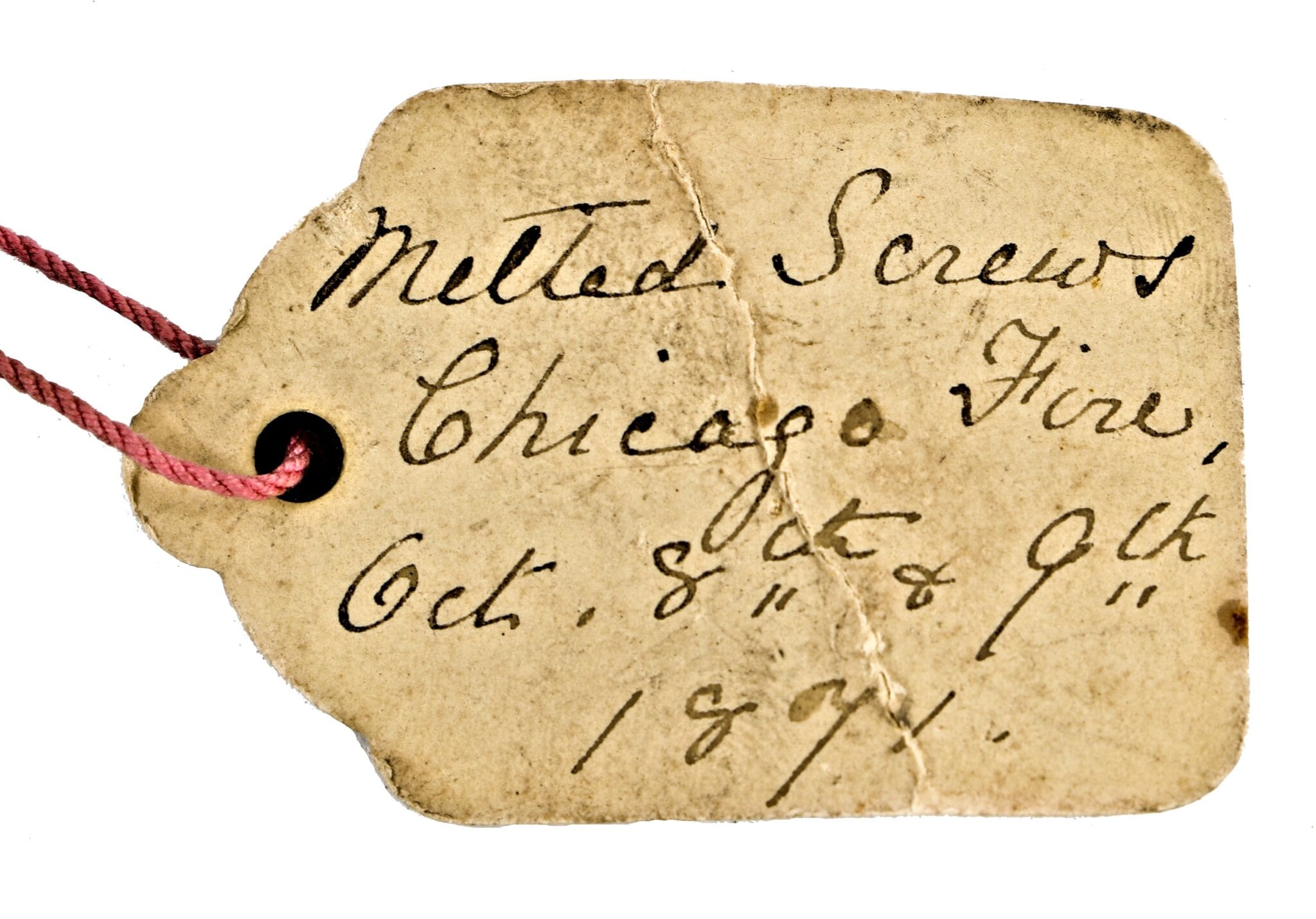

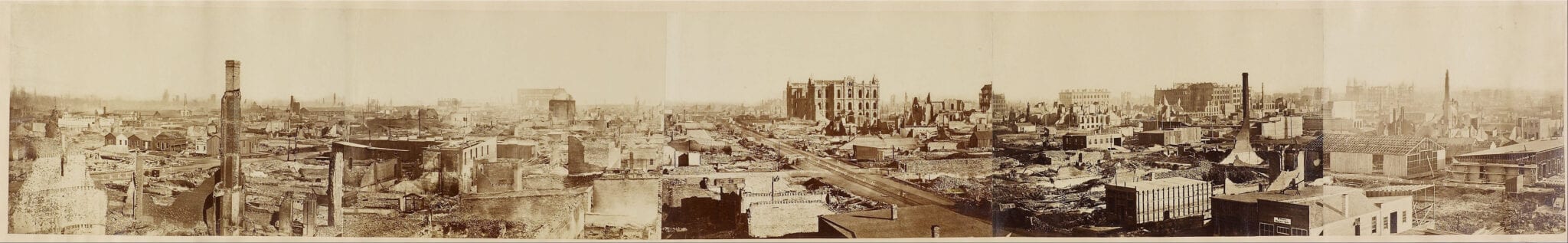

"...this seething ocean of fire, fanned by a hurricane, and fed by the homes and household treasures of a hundred thousand people, everything dissolved—the flames flashing across a street in tongues, as from a compound blowpipe, would pierce a boasted fire-proof structure, and with the speed of thought cut it from front to rear. iron columns melted at the touch, and flamed away in lava to the basement, followed in a crash by the superstructure. marble crumbled into dust, granite swelled with the heat and exploded. limestone flew into fragments, and the fire-proof theories of years vanished in an hour..." - dr. w.b. may, chicago, november 17, 1872.

as dr. w.b. may's description illustrates, the great fire of 1871 thoroughly re-shaped chicago's landscape, with great ramifications on how the burnt district was re-built and altering nearly all materials and industries surrounding construction in the city.

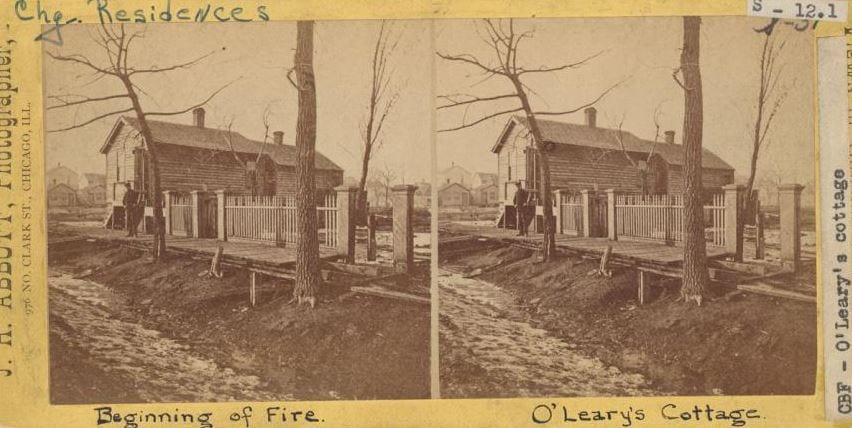

it was estimated that at the time of the fire there were nearly 60,000 structures in the city. over 90 percent were constructed of wood with the great majority being "small cottages" followed by office blocks. on november 23, 1871, the fire limits were fixed: within the boundaries established by the city's common council, wooden buildings were absolutely prohibited. negligence was considered "criminal", and understandably so, considering the severity of the devastation. eventually the restriction on wooden buildings extended to the entire city. meanwhile reconstruction had begun almost immediately, with plans arising before the fire was even extinguished. between 1872 and 1879 more than 10,000 construction permits were issued and between 1871 and 1891 over $316 million had been poured into the construction of new buildings. in 1873, despite a national recession, chicago celebrated its resurgence by hosting the inter-state industrial exposition, promoting chicago and the northwest regions.

taking a closer look at the materials used to construct the burnt district, it seems that a preponderance of post-fire buildings were comprised of brick, a result of the difficulty in obtaining stone. in the distant quarries and carving facilities, demand had quickly outstripped supply, and consequently there were great delays in providing material.

another curious shift in construction to note is that iron fronts became unpopular after the fire, since communities had witnessed the metal warp and twist. even so, single story columns did not dwindle in use.

very little granite was used in most of the post-fire buildings erected immediately after the fire - and this applies both within and outside the limits of the "burnt district." limestone and sandstone were by far the predominant materials relied upon, however, those too were materials that had been witnessed crumbling during the conflagration. the early stages of reconstruction were marked by strong suspicion of materials whose properties had previously been trusted as durable. when remnants of the buildings were surveyed, newspaper accounts from the time reported that "limestone seemed as though [it] actually burned like wood." this impression notwithstanding, no materials could have survived a heat sufficient to fuse metals that are normally infusible (at temperatures below 3000 degrees). these stones and structures would likely pass or withstand temperatures from an ordinary fire, but not the intolerable heat of the city's flames as demonstrated after taking a glimpse at the large area of the "burnt district." interestingly, of the buildings exposed to the fire, the customs house, court house, and first national bank suffered the least damage - all limestone structures.

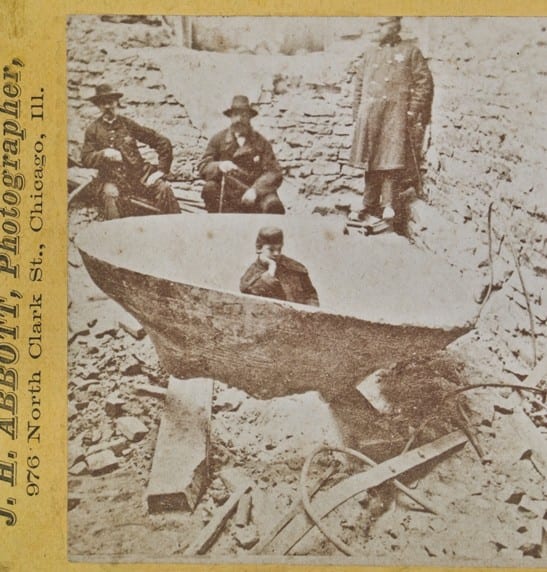

several of the massive solid limestone ball finials were salvaged and a few can be found on display in chicago. in fact, one was in an auction a year ago, but the lot was "passed" on.

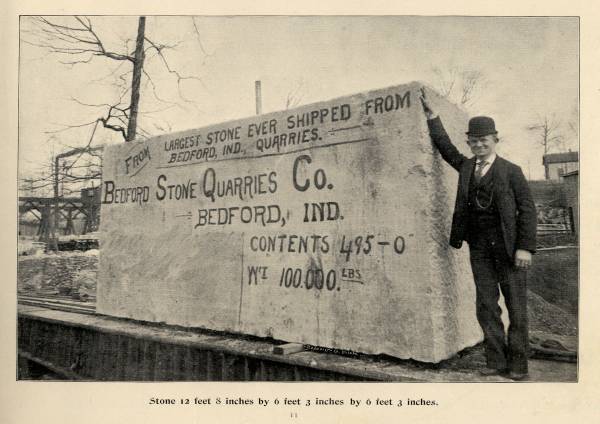

in the end a total of 7 known quarries were charged with furnishing stone during the rebuild. three were based in ohio, one in michigan, and 3 in illinois. the colors of stone varied between white, gray, blueish-brown, reddish-brown and cream. a stone known as "sugar run dolomite," which was unique to quarries in joliet, lemont, and lockport, ills. was used extensively for constructing the foundations and facades of chicago's downtown commercial buildings and/or business blocks during the mid- to late 1800's. perhaps the most notable structure made entirely from this type of stone is the extant chicago water tower and pumping station. by the early 20th century the use of this type of stone had all but disappeared, replaced in large part by limestone quarried from bedford, indiana.

salvaged from an 1872 four-story loft building located at 128 w. lake street (demolished in 1982). the building was erected by contractor charles busby. unidentified architect.

comparatively little mention is made of artificial stone, though it was relied upon as an alternate material for some post-fire building. for instance, j.v. farwell & company constructed the walls of their store from cement. the walls were erected between frames of lumber and the interstices filled with fragment of brick, broken stone , etc., before the liquid cement was poured into the frame. as it cooled, it formed a solid wall and assumed the ornamental forms that had been carved into the wood framing.

material comparison: "artificial stone" (left) and joliet limestone (right)

strictly speaking, artificial stone, also termed "cast" or "concrete" stone, is a synthetic product that was used mainly during the 18th and 19th centuries to imitate natural building stones. an aggregate of water, natural cement, lime, sand, and/or various binding agents, the concrete mixtures could be incorporated in construction as molded shapes and intricate decorative elements or as plain blocks. with various basic mixtures, production processes, and methods of finishing the cast stone could be employed to imitate a wide array of natural materials. a light cement matrix with crushed marble could replicate limestone, while a mix of marble and small amounts of melting slag would give the effect of white granite; the addition of masonry pigments could imitate variegated sandstone. some of the earliest formulas were created in britain, with coade stone produced from 1769-1833, and a patent process in 1844 of a formula by frederick ransome. additionally, coignet stone and frear stone (created by chicagoan george frear) were patented several years prior to the great fire of chicago.

according to an 1872 publication, timothy wright, one of the pioneers of chicago, held a large interest in the ownership of the ransome patents, but his inability to secure an expert in its manufacture prevented him from producing it. eventually, in 1872, he purchased 2 acres south of the city and succeeded in his business of making ransome stone, producing 10 tons of the stone per day. unfortunately, difficulty in filling orders for machinery delayed business, though he was able to demonstrate the success of the stone to many architects during which time nearly 100 tons was turned out. the stone was employed in flouring mills, as window heads and sills, keystones, vases, flooring tiles, and mantels. though the inventor frederick ransome never promoted the stone as fireproof, it was well-known from testing to be a superior, fire-resistant mixture.

prior to the fire of 1871 (following the civil war), artificial stone had gained traction in becoming a commonly accepted, economical substitute for natural materials. the use of cast stone grew rapidly into the early twentieth century, sometimes comprising the only exterior facing material for a building, but more often as trim on a rock-faced stone or brick wall.

original "artificial stone" facade fragment removed from the adams and osborne demolition site, courtesy of the bldg. 51 museum. additional pieces are being donated by the national wrecking company.

certain types of artificial stone were made to be practically non-porous, and thus especially resistant to corrosion from salty or polluted air. it's curious that the material did not gain more popularity, considering it was an inflammable and durable replacement for the wood and limestone which were now suspect building materials. today, buildings of that era constructed with artificial stone are much rarer, and are well-represented by structures like the osborne & adams building that has since been reduced to rubble.

This entry was posted in , Miscellaneous, Bldg. 51, Events & Announcements, Featured Posts & Bldg. 51 Feed on December 10 2019 by Eric

WORDLWIDE SHIPPING

If required, please contact an Urban Remains sales associate.

NEW PRODUCTS DAILY

Check back daily as we are constantly adding new products.

PREMIUM SUPPORT

We're here to help answer any question. Contact us anytime!

SALES & PROMOTIONS

Join our newsletter to get the latest information